plastic_phasefield#

In the proposed model, the total free energy is postulated to have the form of a Ginzburg-Landau free energy functional accounting for interfaces through the square of the order parameter gradient. The total free energy \(F\) of the body is then defined by the integral over the volume \(V\) of a free energy density \(f\), which can be split into a chemical free energy density \(f_{\rm{ch}}\), a coherent mechanical energy density \(f_{u}\), and the square of the order parameter gradient:

\(V_k\) is the set of internal variables for the phase \(k\) in order to describe the hardening state in each phase and \(\ten{E}^e\) is the effective elastic strain tensor.

The irreversible behaviour is described by the introduction of a dissipation potential, which can be split into three parts, which are the phase field part \(\Omega_{\phi}(\phi,c)\) , the chemical part \(\Omega_c(\phi,c)\) and the mechanical dissipation potential \(\Omega_{u}(\phi,c,\ten\sigma, A_k)\):

\(A_k\) is the set of thermodynamic forces associated with the internal variables \(V_k\) and \(\ten\sigma\) is the effective macroscopic strain for the phase \(k\).

The chemical free energy density \(f_{\rm{ch}}\) of the binary alloy is a function of the order parameter \(\phi\) and of the concentration field \(c\), which is much more described in the \(<\)ENERGY\(>\) section. The second contribution to the free energy density is due to mechanical effects. Assuming that elastic behaviour and hardening are uncoupled, the mechanical part of the free energy density \(f_{u}\) is decomposed into a coherent elastic energy density \(f_{e}\) and a plastic part \(f_{p}\) as:

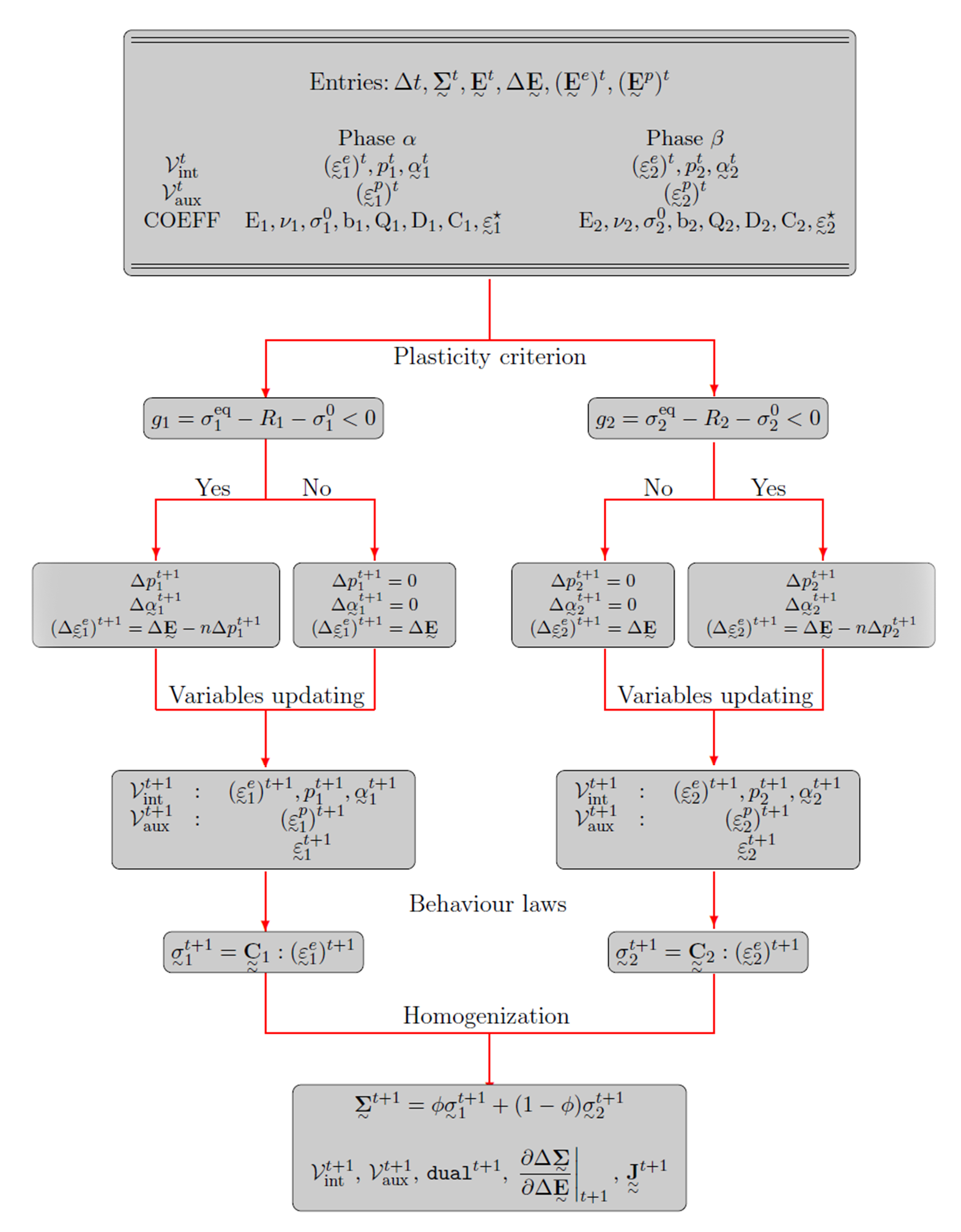

In the proposed model, we consider that the system consists of a two-phase elastoplastic binary alloy \(1\) and \(2\), which are separated by a plane diffuse interface, with one non-linear isotropic hardening and one non-linear kinematic hardening in each phase. The specific free energy taken as the state potential of the material is chosen as a function of all state variables. Assuming again that there is no coupling between elasticity and hardening, the free energy is split into three terms, corresponding to the elastic energy, the kinematic hardening part and the isotropic part. To satisfy the condition of thermodynamic stability, it is sufficient to choose a positive definite quadratic function in the components of elastic strain tensor and all internal state variables as follows:

\(Q_k\) and \(C_k\) are the material parameters for isotropic and kinematic hardening states and \(k =\left\{1, 2\right\}\) corresponding to the two phases. Consequently, the Cauchy stress tensor and the associated thermodynamic force variables \(\ten X\) and \(R\) for the phase \(k\) are deduced as follows:

The partition hypothesis requires a decomposition of the total strain in each phase into elastic, eigen and plastic parts:

where the local parameter for each phase may depend on the local concentration \(c\), but not on order parameter \(\phi\).

Furthermore, the mechanical dissipation is assumed to be due to three mechanisms: the inelastic strain, the kinematic hardening and the isotropic hardening. Thus, the dissipation potential can be split into a plastic contribution, which is called the yield function, a nonlinear kinematic hardening term and a nonlinear isotropic hardening term and can be expressed as a convex scalar valued function as follows :

Assuming that the elastoplastic phase field behaviour of each phase is treated independently, we define a yield function for each phase as:

with \(\sigma_k^0\) is the initial yield stress, \(\sigma_k^{\rm{eq}}\) is the von Mises equivalent stress and \(\ten s_k\) is the deviatoric stress tensor.

According to the normality rule for standard materials, the evolution laws of the internal variables are derived from the dissipation potential. For phenomena which do not depend explicitly on time, such as rate independent plasticity, the potential is not differentiable. Then, the partial derivative of \(\Omega_k\) with respect to \(g\) is simply replaced by a plastic multiplier \(\dot \lambda\) to write a rate independent plastic model. Consequently, the evolution laws can be expressed as:

where \(\ten n_k =\partial g_k /\partial {\ten \sigma}_k\) is the normal to the yield surface and defines the flow direction and the plastic multiplier \(\dot \lambda\) is determined from the consistency condition \(dg_k/dt=0\) 1The first consistency condition, \(g_k=0\), means that the state of stress is on the actual yield surface, the second \({\dot g}_k=0\), means that an increase of the state of stress stays on the yield surface. Elastic unloading occurs when \(g_k <0\) or \({\dot g}_k <0\) , the internal variables then keeping a constant value..

The elastoplastic and phase field behaviours of each phase are treated independently and the effective behaviour is obtained using homogenization relation. In the proposed model, the Voigt’s scheme is used, where the basic assumptions are that the strain field is uniform among the phases at each material point. Using Voigt’s model, we assume a uniform total strain at any point in the diffuse interface between elastoplastically inhomogeneous phases. The effective stress is expressed in terms of the local stress average with respect to both phases weighted by the volume fractions:

The stresses of both phases \(\ten\sigma_1\) and \(\ten\sigma_2\) are given by Hooke’s law for each phase:

where \(\tenf C_1\) and \(\tenf C_2\) are respectively the tensor of elasticity moduli in \(1\) and \(2\) phases.

The stress at any point in the interface is computed from the average of the above local stresses as follows:

From the above relation, it follows that the strain-stress relationship in the homogeneous effective medium obeys Hooke’s law with the following equation:

where the effective elasticity tensor \(\tenf C_{\rm{eff}}\) is obtained from the mixture rule of the elasticity matrix for both phases:

and the effective eigenstrain \(\ten{E}^\star\) and plastic strain \(\ten \varepsilon^p\) vary continuously between their respective values in the bulk phases as follows:

In the case of nonhomogeneous elasticity, it must be noted that \(\ten{E}^\star\) and \(\ten \varepsilon^p\) are not the average of their respective values for each phase.

According to the Voigt homogenization theory, the local energy stored in the effective homogeneous elastic material is expressed in terms of the average value of the local elastic energy with respect to both phases weighted by their volume fractions:

Similary, the irreversible part of the mechanical behaviour for effective material is defined with respect to the mechanical dissipation potentials \(\Omega_{u1}(c,\ten\sigma_1, A_1)\) and \(\Omega_{u2}(c,\ten\sigma_2, A_2)\) for \(1\) and \(2\) phases respectively by means of the shape function \(\phi\) as:

Stored Variables

prefix |

size |

description |

default |

|---|---|---|---|

|

S |

the concentration |

yes |

|

S |

Order parameter |

yes |

|

V |

Concentration gradient |

yes |

|

V |

Order parameter gradient |

yes |

|

V |

Concentration flux |

yes |

|

V |

Microstress |

yes |

|

S |

Internal microforce |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Cauchy stress |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Total (small deformation) strain |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Elastic strain |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Effective inelastic strain |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Cauchy stress |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Inelastic strain for the first phase |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Elastic strain for the first phase |

yes |

|

T-2 |

kinematic hardening internal variable for the first phase |

yes |

|

V |

cumulated plasticity equivalent for the first phase |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Cauchy stress |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Inelastic strain for the second phase |

yes |

|

T-2 |

Elastic strain for the second phase |

yes |

|

T-2 |

kinematic hardening internal variable for the second phase |

yes |

|

V |

cumulated plasticity equivalent for the second phase |

yes |

***behavior plastic_phasefield

\(~\,\) **energy <ENERGY>

\(~\,\) **kinetics

\(~\,~\,\) *mobility <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,\) **chemical_interpolating_function val

\(~\,\) **mechanical_interpolating_function val

\(~\,\) **homogenization [name]

\(~\,\) **phase1

\(~\,~\,\) *elasticity1 <ELASTICITY>

\(~\,~\,\) *eigen_coeff1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *delta1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *c_ref1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *plastic

\(~\,~\,~\,\) R01 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) B1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) Q1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) C1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) D1 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,\) **phase2

\(~\,~\,\) *elasticity2 <ELASTICITY>

\(~\,~\,\) *eigen_coeff2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *delta2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *c_ref2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,\) *plastic

\(~\,~\,~\,\) R02 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) B2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) Q2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) C2 <COEFFICIENT>

\(~\,~\,~\,\) D2 <COEFFICIENT>

**phase1Definition of the material elastic parameters and eigenstrains induced by variation of concentration. The eigenstrains are defined as follow

\[\ten{\epsilon}^* = ({\tt eigen\_coeff1} + {\tt delta1} (c- {\tt c\_ref1} )) \ten 1\]**phase2Identical as

**phase1

***behavior plastic_phasefield

**energy kim

*phase1

c1 0.7

b1 0.0

k1 1.

D1 0.1

*phase2

c2 0.3

b2 0.0

k2 1.

D2 0.1

*interface

energy 1.

thickness 0.25

zeta 0.05

ENER 0.5

**kinetics

*mobility 1.

**chemical_interpolating_function 1.

**mechanical_interpolating_function 1.

**phase1

*elasticity1

young 70000.

poisson 0.3

*eigen_coeff1 0.001

*delta1 0.0015

*c_ref1 0.

*plastic

R01 15.

B1 0.

Q1 0.

C1 0.

D1 0.

**phase2

*elasticity2

young 70000.

poisson 0.3

*eigen_coeff2 0.000

*delta2 0.0015

*c_ref2 0.

*plastic

R02 70000000.

B2 0.

Q2 0.

C2 0.

D2 0.

***return